Jenn Marshall & Kathleen Miller, Contributing Writers, Health+ Studio

This is the first in a series of six blog posts that each focus on a key ingredient to strengthen cross-sector partnerships to successfully address SDOH and advance health equity in communities.

Effectively addressing social determinants of health (SDOH) and promoting health equity in communities requires an intentional focus on cross-sector partnership among public health, health care, and community-based organizations (CBOs). In this blog post, we'll describe structures that cross-sector partnerships can put in place to set themselves up for success.

Defining the right partnership structure

A multisector partnership can take many different forms. The structure that will work best for a particular partnership depends on many factors, including the goals and maturity of the partnership. These partnership structures are not static; they can vary by initiative or partner or change over time.

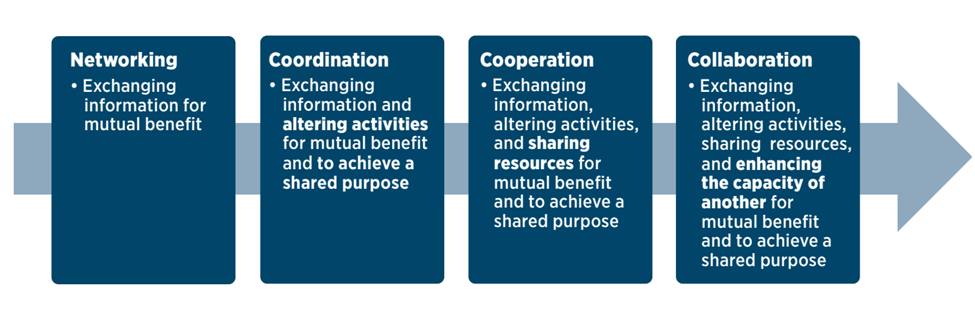

The toolkit for Building Non-Traditional Public Health Multisector Partnerships from the Association for State Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) offers a useful way of thinking about various partnership structures. Partnerships typically fall along a spectrum that includes (1) networking, (2) coordinating, (3) cooperating, and (4) collaborating. The progression from networking to collaborating signifies a deeper intensity, which may entail an increasing level of formality. Each approach to engagement can contribute to building partnerships that address SDOH and root causes of inequities.

Partnerships spectrum

Adapted from ASTHO’s toolkit for Building Non-Traditional Public Health Multisector Partnerships.

The first approach, networking, is where many partnerships begin. Networking provides information and insights, but this relationship doesn’t extend to coordinated action. For example, a hospital and local public health department could meet to share their respective strategies for diabetes prevention and control and learn from one another, or a clinic could invite community-based food pantries to speak about their services at informal learning lunches.

The next level, coordination, includes networking and also involves partners working together to plan and tailor their individual activities so their efforts work well in tandem. For example, a public health department could invite the local hospital and a CBO to contribute to its Community Health Improvement Plan, with the goal of identifying existing social connectedness programs and understanding their reach within the community better so as not to duplicate efforts.

Further along the spectrum is cooperation, which builds on networking and coordinating and adds the capacity to share data, staff, services, and other resources. Sharing resources formally or informally enables partners to accomplish things that any one organization couldn’t do on its own. For instance, a cooperating partnership might establish technology platforms or other mechanisms for sharing data, such as tobacco cessation program participation rates, number of referrals to housing assistance services, or the prevalence of food insecurity identified by screening patients for social needs.

Collaborating partnerships, the most complex and least common partnership structure on the spectrum, may be most effective to achieve long-term, sustainable change. Collaboration is unique because helps build partners’ capacity for additional or more effective work. It can have a multiplier effect, strengthening each partner’s work while also advancing new joint efforts. For example, a collaborative partnership might apply jointly for grant funding. Or partners might co-design and implement programs, services, and policies on shared priorities. For example, Proviso Partners for Health and the Real Foods Collective in Maywood, Illinois, collaborated to align the work of multiple CBOs in the community to expand the reach of food distribution and nutrition education more broadly.

|

In some cases, partnerships may benefit from a formal agreement or memorandum of understanding (MOU) that defines relationships, roles and responsibilities, expectations, measures of accountability, and decision-making processes. Ask partners questions to facilitate developing this kind of agreement:

● What do members expect from this partnership?

● How will we each be held accountable for the work and outcomes?

● How will decisions be made?

● How can we build trust and a shared language and understanding?

Cross-sector coalitions addressing community SDOH can use the Community Research Collaborative’s partnership agreement template to develop a MOU.

|

Remember, no one structure is better or worse than another. Networking, coordinating, cooperating, and collaborating each have benefits and drawbacks; the key is to select the structure that is best suited to achieve your partnership’s goals. In our next post, we’ll dive into strategies that partnerships across the spectrum can use to support and sustain efforts to improve SDOH in communities.